The Fourfold Root of Stoic Virtue

The Foundation for a New Stoicism

“When someone consulted Epictetus about how he could persuade his brother to stop being ill-disposed towards him, he said: Philosophy doesn’t promise to secure any external good for man, since it would then be embarking on something that lies outside its proper subject matter. For just as wood is the material of the carpenter, and bronze that of the sculptor, the art of living has each individual’s own life as its material.”

Epictetus, Discourses, 1.15

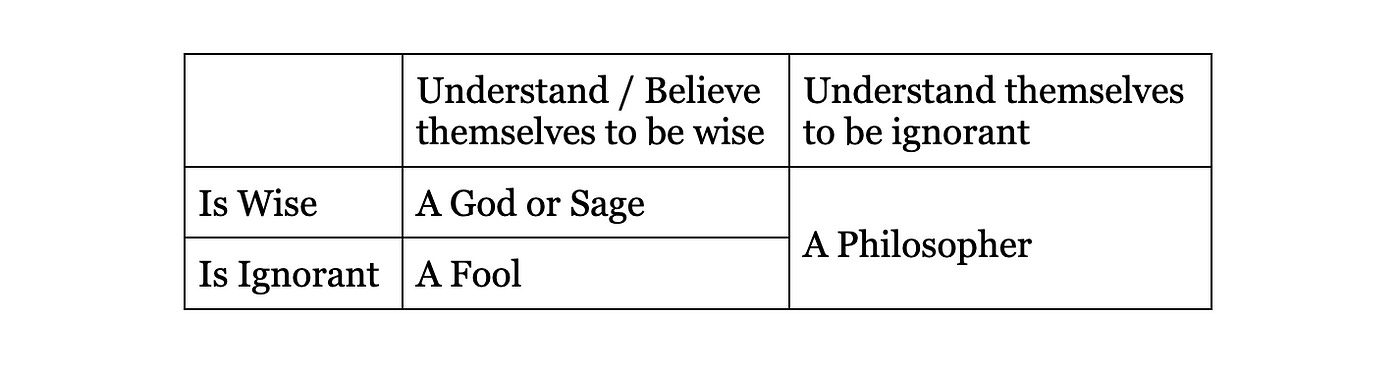

Ancient Stoicism makes a stark distinction between the sage and the non-sage. The sage possesses an abundance of wisdom sufficient to give them the self-coherence that mirrors the self-coherence of the cosmos — the whole of nature. According to ancient Stoic doctrine, sages are equal to gods if they achieve this level of mastery over the self.

The approach to wisdom, then, isn’t quantitative. There are no degrees of “wise”. There is no quantity of “wise” that fills our minds in greater or lesser amounts as water fills a jar. There is wise and there is not-wise.

This is a crucial aspect of Stoic philosophy since it determines the thematic of the Stoic’s practice. Sages are rare — perhaps impossible — and so sagehood serves more as a guiding star than an attainable goal to Stoics.

Below the status of sagehood is the status of the non-sage, divided in two ways — those who are ignorant but think they are wise, and those who are ignorant and understand that they are ignorant.

Ignorant people who believe themselves to be wise are fools, not much more can be said about them. Those who are ignorant and understand that they are ignorant are philosophers. The model for this formulation is, of course, Socrates. Since he understood himself to be ignorant, Socrates attained wisdom in moments.

Socrates himself compared the figure of the philosopher to Eros. Eros loves beauty because Eros is not beautiful. Eros therefore seeks and follows beauty, hoping to attain it. In the same way, the philosopher seeks and follows wisdom.

As Eros loves beauty, the philosopher loves wisdom — after all, the very meaning of philosophy is the “affection” (φίλο) of “wisdom” (σοφία) — and aspires to be wise.

The philosopher is guided by reason, without sharing in (or mirroring) the self-coherence of the cosmos like a sage or a god. Philosophers oscillate between being ignorant and wise from moment to moment.

As such the philosopher is guided by probable reason — though reason they determine what they think is probably the right course of action in a given situation.

If the intent corresponds to the rational course of action, or the Stoics’ “will of universal nature”, then in the moment of the decision, that person is wise. If their intent does not correspond to the will of universal nature or the rational course of action, then they are still ignorant, but in the moment of deliberation they were wise.

Philosophy, then, is a practice, not a theory. We “do” philosophy by exercising reason. But studying theory is undoubtedly important in the journey of attaining wisdom, since wisdom can be transmitted through words.

Three Movements of the Soul

The vast majority of Stoic literature has been destroyed either deliberately or through decay. We have no full record of the work of the most influential Stoics of the ancient world — philosophers such as Chrysippus, Panaetius, and Posidonius — only fragments of their writing or sayings quoted in later texts.

These philosophers wrote hundreds of books between them, laying out the Stoic doctrine that spread through the Greek and Roman worlds.

Of the Stoic books that survived decay and libricide — from Seneca, Marcus Aurelius and Epictetus and all written in the later Roman era of Stoicism — none were explicitly instructive of Stoic doctrine.

Epictetus is the Stoic from whom we can best understand the philosophy’s doctrine since Epictetus was a philosopher first and foremost. The Discourses and the Handbook, compiled from remarks in discussions after theoretical classes, give us the most systemic and orthodox explanation of Stoic principles from a Stoic.

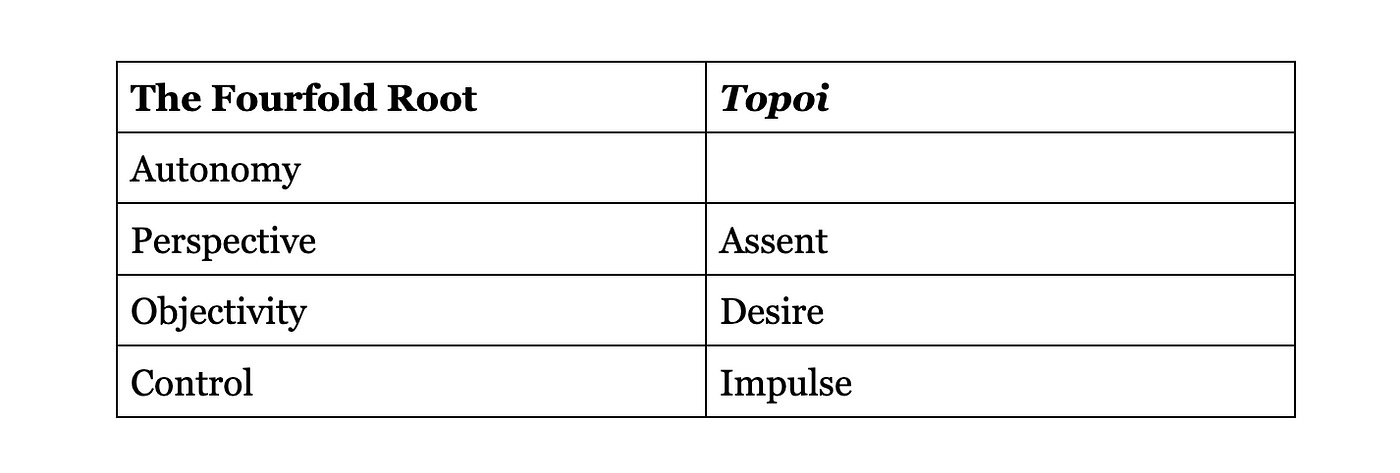

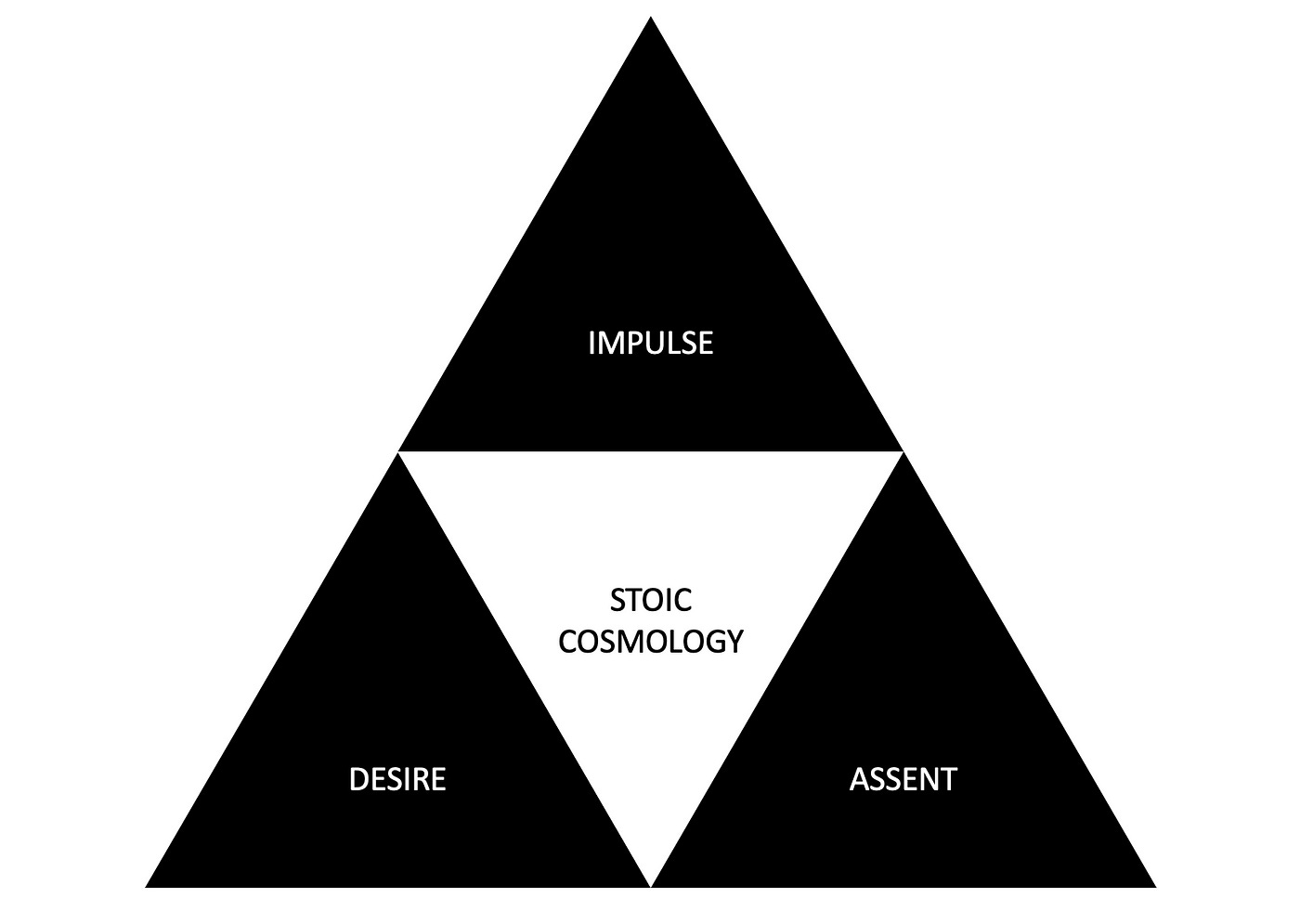

Epictetus had developed three topoi — “areas” or themes — of discipline that correspond to three “movements of the soul”. These topoi were central to the orthodox teaching of Epictetus.

As such, they structure the philosophical reflections in the Meditations of Marcus, who very likely was taught in the Epictetan tradition and mentions “the three exercise themes, or rules of life, set fourth by Epictetus.”

The topoi and corresponding “disciplines” are as follows,

The area of assent

Ultimately, we choose our value judgments — we have the power to judge or opine about everything we can possibly know. Nothing in the world is good or evil, or right or wrong in itself — it is in our minds that we make these judgments. All events and things outside of the human soul is “indifferent”. The soul judges alone and only the soul can be good or bad in turns.

The discipline of assent

Epictetus encourages us to critically examine our judgments, question their validity, and only give assent to those that align with reason and virtue. Think of assent as a gatekeeper at the portal of your consciousness. What do you let in? Only an objective description of what appears to your senses is wise.

To judge something as “terrible” is unreasonable since nothing in-itself is terrible. Only your thoughts can be terrible. As Epictetus said, “It is not events that disturb people, but their judgements concerning them.”

The area of desire

We have control over our desires and aversions and should therefore understand them. What makes us want some things and avoid others? There is a double bind at the heart of most people’s desire — we believe we need more pleasure to be happy, but when we don’t attain it, we only feel more pain. If we didn’t seek what is unreasonable to seek, we’d naturally feel an abundance of pleasure and happiness.

The discipline of desire

By aligning our desires with what is within our control and cultivating indifference toward that which is outside of our control we can achieve equanimity. To maintain discipline over desire is to love the fate that the cosmos hands to us, and not to pine for what doesn’t come our way.

The area of impulse

The human being has agency — the power to act on their thoughts to affect change. How we react to some event is up to us. Our values and dispositions guide our actions, which have consequences for other people.

So how ought we act? The Stoics had the notion of oikeiôsis — roughly translated as “affinity”. Oikeiôsis is what is natural to each species. Living creatures have a preference for things that preserve and propagate them, and an aversion to whatever threatens their integrity.

The oikeiôsis unique to the human being, according to the Stoics, is reason — it is what naturally distinguishes human beings. Acts that are appropriate are acts according to reason.

The discipline of impulse

Epictetus teaches us to act according to reason, not to act emotionally or by instinct. Appropriate actions are aligned with human oikeiôsis, they are good in intent even if they are indifferent in reality, as all events and things are “indifferent” — neither intrinsically good nor intrinsically bad — to the Stoic.

Good acts are those that recognise and intended to serve the community of human beings. Marcus describes the “usefulness” particular to each of us in service of the human community. It’s natural for human beings, being a social species, to form a community, and natural that our usefulness is in service of the community.

But it is possible to do bad, even with good intentions. In the absence of certainty of the outcome of our actions, the Stoic is guided by probability based on what is known to them at the moment of action. The very act of deliberation, being rational, is good in itself.

It’s worth expounding this particular discipline because it tackles a paradox in Stoic thought — if all happenings in the world are indifferent and determined by providence, then what use are our actions? Related to this — what good are our actions if good were only possible in thought?

In the discipline of action, it is the intent — which is in the domain of the soul and therefore free — that makes the action worthwhile. The actions of the stoic are therefore inwardly directed and validated in the interests of achieving apatheia — peace of mind — that follows virtue.

This is what Marcus means when he writes, “I always take the present moment as raw material for the exercise of rational and social virtue.” The Stoic has the means to achieve virtue — moral perfection — at every moment of their life, they don’t have to wait for any well-intentioned actions to come to fruition in time.

This is why the present moment is so important in Stoic philosophy — it is only the present that actually matters. The past and the future are temporal realms for the indifferent, the present alone holds the opportunity for salvation.

The action itself is not good in-itself, it is indifferent just like everything else outside of the mind (or soul). But if the action is a result of a pure intention toward the good, it has already achieved its goal, regardless of what fate has in store for that action.

In this way, our actions can be spoiled but nothing in the world can stop our intentions. If our intentions are indeed frustrated by destiny then we have the opportunity to practise another virtue — accepting destiny with equanimity, with the peace of mind that our intentions were for the best.

Marcus continues in that same passage to write — “Because a god or man can assimilate anything that happens: it will not be new or hard to handle, but familiar and easy.” Every obstacle and setback is simply fuel to the fire of reason, if reason is properly exercised.

A Fourth Movement of the Soul

Hadot sees these themes laid out from the outset of the Handbook of Epictetus, a book recorded for posterity by Arrian of Nicomedia, one of the philosopher’s pupils.

In this book, Epictetus is recorded as saying,

“What depends on us are value-judgments, impulses toward action, and desire or aversion; in a word, everything which is our own business. What does not depend on us are the body, wealth, honors, and high positions in office; in a word, everything which is not our own business.” (E. 1.1 Trans. Hadot/Chase, my emphasis)

In the first sentence here Epictetus delineates what is within our control — our judgements, our impulses, and our desires and aversions. What he lists corresponds to the three movements of the soul and the topoi of philosophical exercise. Everything that is not in our control falls outside of the three topoi.

The problem with this tripartite system of Stoicism is that it is based on a fourth topos, one at the centre of the ancient Stoic system — the assumed existence of divine providence.

In the same passage of the Handbook, Epictetus goes on to describe these three human faculties as “naturally” free. That is, they are free in a cosmic sense, while everything else is “frail, inferior, subject to restraint — and none of our affair.”

Epictetus is making a judgement here, distinguishing between that which is free and sovereign — our participation in the rational nature of God though the three movements of the soul, and that which is “frail” and “inferior” — the course of events and the matter from which we are made.

When Epictetus describes these “free” faculties, he tells us that God made us our bodies as “cunningly constructed clay” which does not belong to us, since it is inert matter. But in the human soul — and here Epictetus is speaking as if he is God — “I have given you a portion of myself […] the power of positive and negative impulse, of desire and aversion.” This is why Epictetus qualifies the word “free” with “naturally”.

It is thanks to God, in Stoic philosophy, that we possess, in Hadot’s words, “an islet of autonomy, in the midst of the vast river of events and of Destiny.” Stoic cosmology — the oneness of the universe, that God and the universe are one — therefore underpins human autonomy.

The three movements of the soul belong to the soul and are therefore free. This is why three disciplines correspond to these movements. One must maintain discipline over that which one can control — to have discipline over what you cannot control would be senseless.

It’s worth reminding ourselves of the Stoic cosmology at this point. All the cosmos is of God, therefore all is One. The changes of the cosmos are guided by providence through the divine “Logos” of God. All matter is animated by the logos through God’s breath — pneuma.

All living things have a greater or lesser amount of pneuma. Human beings have the most among all animals, and so the human being is rational, sharing in the rational order of the cosmos. While human beings have no control over the fate of their bodies, they have the capability to understand the workings of the universe.

As Epictetus put it, “Other beings lack the capability of understanding the divine administration; but rational beings possess the inner resources which allow them to reflect upon this universe. They can reflect that they are a part of it, and on what kind of a part they are; and that it is good for the parts to yield to the Whole.” (D 4.7.6)

Through this understanding, human beings choose how they conduct their lives. Living “in accordance with nature” — mirroring the divine logic that guides all things — is finding equanimity (Apatheia), tranquillity (Ataraxia) and the virtue that comes with living up to your potential (Arete).

In the previous essay, “The Stoic Self”, the Stoic notion of divine providence is untenable if Stoicism is to truly flourish in the 21st-century world. Yet, equally, modern Stoicism does not provide a philosophy of self-coherence since it jettisoned the ancient Stoic cosmology without substituting it.

Both ancient Stoicism and modern Stoicism rest on belief systems. Ancient Stoicism constructed its own cosmology at the foundation of its three pillars of logic, physics and ethics. Modern Stoicism is an ethical system alone, based on what could be salvaged of ancient Stoicism, that effectively outsources its normative and cosmological underpinnings to prevalent secular beliefs and tacitly approved science. What we are left with resembles therapy more than philosophy.

Ancient Stoicism’s internally coherent cosmology serves to give a “why” to every ethical theorem. It is Stoic to say “treat all people with respect.” It would seem strange to ask why we should do so, because politeness and decency demand that we treat all people with respect.

But the Stoic doesn’t say “treat all people with respect” in deference to social norms, because social norms can, and do, change. A Stoic would treat all people with respect because they understand that all human beings carry within them a quantity of the fiery pneuma — “divine breath” — that makes all human beings part of God and in communion with God’s divine logic through reason.

So we should treat people with respect because, at the most fundamental level, we are of the One. To insult another person is — ultimately — to insult yourself. This idea is what grounds Stoic ethical ideas in a coherent and cohesive worldview that we can call “philosophy”.

The modern Stoic would point to interpersonal respect as an obligation of a social existence, or perhaps suggest that rational altruism is evolved into human nature. While all these reasons are aligned with the desired outcome, the modern reasons are contingent and conditional, while the ancient reason is absolute and properly universal.

The seamless linkage between a theory of existence and the way to conduct oneself allowed the ancient Stoic a sense of absolute conviction — best described as “acceptance” — in their duty as a citizen of the world.

Plutarch quotes Chrysippus as writing,

“There is no more appropriate way to arrive at the theory of goods and of evils, virtues and wisdom, than by starting out from universal Nature and the organization of the world […] for the theory of goods and evils must be connected to these subjects […] physics is taught only so that we may be able to teach the distinction which must be established between goods and evils.”

The modern Stoic would counter that modern science is consistent with ancient Stoicism through the widely accepted belief in the modern world of natural laws that underpin causality — the naturally consistent way that all things behave.

But ancient Stoicism, in its belief in a Divine Logos, the deterministic logic of fate, is actually more akin to the theological idea of “Occasionalism” — the notion that all things are willed by God alone.

In Occasionalism, there are no natural laws, only God’s commands. To the Stoic believer, the Stoic God is no more and no less than Reason itself as a guiding force that is immanent to the whole cosmos. This is why human reasoning stands at the junction of Stoic cosmology and ethics.

While ancient Stoicism’s cosmological and theological underpinnings make it self-sufficient, Modern Stoicism’s resemblance to ancient stoicism is contingent on broadly accepted beliefs staying as they are.

The Fourfold Root

The goal here is a new Stoicism that’s not a matter of belief or received assumptions, but a matter of how one must conduct oneself, no matter what they believe, in the pursuit of moral excellence. Furthermore, this should inspire, by its logical grounding, the same absolute acceptance of moral virtue that ancient Stoicism inspired.

In the “Stoic Self”, we have supplanted Stoic cosmology with the most fundamental aspect of the human condition — the formation of the self. It goes without saying that agency — moral or otherwise — is impossible without some degree of autonomy in the agent.

The human self is a confluence of processes that give rise to the three movements of the soul. The self in Stoic philosophy — reduced to the inner working of the soul, matches the idea that the self is definable only by the choices it makes rather than what it substantially is — a body. We can therefore integrate the Stoic idea of the self without necessarily accepting the wider Stoic cosmology. In short, we are replacing the older Stoic “place of the self in the cosmos”, with a Stoic “predicament of the self”.

As such, a cogent Stoic theory of selfhood, and not ancient Stoicism’s belief system, can form the basis for a universal Stoicism that defers to neither a cosmological theory, nor ideas about the nature of the universe or human beings that are external to the Stoic system as we have with modern Stoicism.

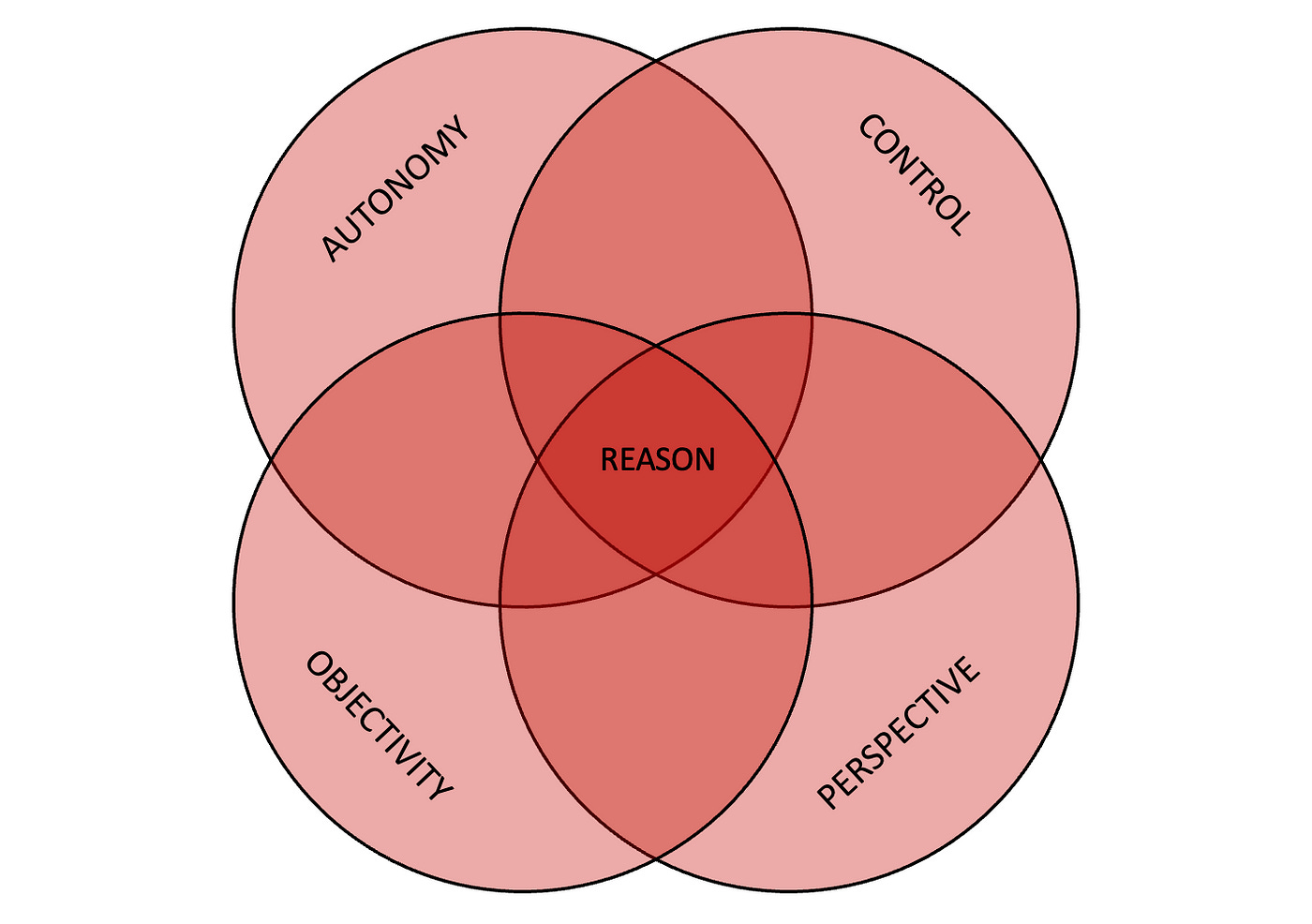

The orthodox themes of Stoic ethics need to be modified in this new reality. Instead of three “movements of the soul” — desire/aversion, judgement and impulse, we now have four aspects of the self, since we need to include the understanding of the self in deliberative agency. This is best described as “autonomy” — the movement of the soul in delimiting itself.

Instead of drawing “disciplines” from these themes in ethical instruction — the “discipline of ascent” and so on, we can reconceive them as a more fundamental root of the new Stoicism — an interconnected foundation from which we can understand the world, without a story about its beginnings or workings. So we shall call this new system, “The Fourfold Root of Stoic Virtue”.

The fourfold root comprises Autonomy, Perspective, Objectivity and Control. The aspects of the fourfold root correspond to Ancient Stoicism’s topoi (themes) as below.

The fourfold root system is properly philosophical since it is a system that promises no certainties such as “there is a God” or “there is no God” or even “there might be a God”. Whether there is a God is up to you to decide, but it would be a matter of belief. There is no sagehood in this system, either, since its basis is not an understanding and acceptance of the workings of the universe, but the tangled uncertainties of being human.

In the coming weeks, we’ll take a closer look at each aspect of the Fourfold Root, starting with Autonomy. We’ll examine exactly why each aspect is essential if we are to find virtue and freedom, excellence and happiness, in a world in many ways different — but in surprising ways the same — as the world in which Stoicism first emerged.

Thank you for reading.