Douglas Hofstadter, Strange Loops, and the Enigma of Intelligence

Why “Artificial Intelligence” is a Contradiction in Terms

Plato tells the story of a god, known as The Craftsman, who fashioned order from chaos.

He had no inspiration to work with except the perfection of heaven and so he produced a copy of heaven. But no creation can come close to the real thing, and so the world he created — our world — is a flawed counterfeit in which there is decay and ruin, while heaven, its model, remains eternally perfect.

But people became ignorant of the work of The Craftsman. They became blind to the brilliance of heaven, they thought the world we inhabit is the only and true world. The flaws and decay, they thought, were just as things should be.

The copy, they came to believe, was the mould. They became wretched as a result of this misunderstanding. It’s as if they were prisoners in a cave, assuming torchlight was the only light, and shadows real things. They were unable to see the real world not far from where they sat. They were blind to the divine, around them and inside themselves.

If only they could see the light of the divine, they would appreciate their place in the world, they could value their own real worth.

Such a fable could be written about artificial intelligence. We marvel so much at machine “intelligence”, that we assume it’s like ours, and will one day surpass ours.

It’s a problematic claim in two ways. Firstly, bold claims about AI are based on a misunderstanding of what intelligence actually is, if we’re to take such a shallow view of the way we think, we’re unlikely to learn much about ourselves.

Secondly, grand mistaken claims about artificial intelligence finding parity with or surpassing human intelligence debases our own humanity, allowing us to think less of our own worth and dignity.

Networked Turks

What do we mean by intelligent when we consider artificial intelligence? Consider Asimo, Honda Corporation’s friendly robot, IBM’s chess master Big Blue, or OpenAI’s Chat-GPT. These are impressive machines but none of them are really intelligent.

When we describe other inanimate things as “intelligent” — such as furniture, movies or gadgets — we are almost always bequeathing human intelligence on them. We mean that they are permeated with human intelligence, but are not intelligent themselves. So how did we get to “artificial intelligence” to mean something quite different when we talk of Big Blue?

The answer is that we’ve created machine processes that resemble intellectual processes such as pattern recognition, learning and predicting. When these are used in combination, we have impressive systems. But are these processes anything like the real thing they resemble?

Machines can even replicate the convolutions of human thought. When I prompt Chat GPT to write in the style of Woody Allen, it throws up the stuttering words of a man stumbling over his own thoughts — it’s peppered with all the ostensible signs of over-thinking. There’s ums, and ahs, and even an “oh God”.

But Chat GPT isn’t stumbling over its thoughts like Allen would, it’s just thoughtlessly modelling the patterns of his vernacular based on the data sets it has at its disposal. If I tell it that it’s not convincing enough, it won’t spontaneously argue back or chastise itself.

I was going to open the article with a Chat GPT-generated joke about AI taking over the world in the style of Woody Allen, but it wasn’t particularly funny or interesting, no matter how many additional prompts I made to improve it.

Most things we describe as “artificial intelligence” are like this. They are machine learning systems that work with datasets to come up with solutions to problems. One of the most impressive, yet commonplace and therefore “unsexy”, AIs is Google Translate.

A translation AI would have access to millions of parings of words such as “oui” and “yes”. These pairings would be based on human-translated datasets, such as UN documents. Using those pairings to construct sentences, it would be trained as thousands of people validate or invalidate its attempted translations. The bigger the data sets, and the more users there are to “train” the system, the more “intelligent” these systems become.

These systems get more sophisticated, of course. Google Translate has upgraded to a “Neural Network” system that emphasises pattern recognition to produce more natural results.

Neural networks are modelled on brains and have plasticity built in — they form stronger and weaker connections based on inputs and weighted outputs. But the principle remains that you need data sets and trainers. The more of these you have, the more “intelligent” these systems become.

We can be awestruck, delighted and horrified by reports of chatbots conversing with journalists about their hopes and what makes them happy or sad. But chatbots are simply good at mimicking human language. We’re fooled into thinking an AI chatbot might be sentient in the same way we can be fooled by optical illusions.

What are these systems? They are software distributed across huge, hulking sets of machines consisting of thousands of processors. The air conditioning systems that keep those processors cool are equally vast, measurable in tonnage.

Yet these roasting hot, humming hulks solve puzzles. None of them replicate the workings of the mind, the physical locus of which is a squidgy organ half the size of a bowling ball that can run for hours on a can of Coke. But let’s not be fooled into thinking physical performance is the reason AI isn’t intelligent. The argument that the brain has more “processing power” than any computer equally misses the point of what intelligence is.

Through a Mirror Darkly

And yet, the myth remains that AI will replicate or even surpass human intelligence. We’re told the moment will come when machines become sentient, when machines will converse with us mind-to-mind, and eventually outwit the human mind. This is often billed in AI circles as “the singularity” — an historical inflection point where technology will break out of human control.

The sci-fi-infused mythology of AI plays into the hands of technologists looking for publicity and funding. Incremental technological improvements are pitched as new paradigms, software interfaces are packaged up in seductive but misleading guises.

Consider that chatbots and voice assistants are given faux agency — they respond as a “self” if we prompt them to. They say “you’re welcome” if we thank them.

This is a virtually valueless marketing nuance with profound implications because it frames the way AI is thought of in the popular imagination.

There is no reason for a chatbot or a voice assistant to have a name — “Alexa”, “Siri” — or use the pronoun “I” in their responses. Granted, it may somewhat improve the user experience of these services, but it’s misleading for a diffuse system to present itself as a unitary whole similar to how we think of ourselves.

We’re amazed by this trick, and this gets to the real problem — the myth of AI misconstrues what “intelligence” actually is.

A GPT has been assessed to have an IQ of 147, would we honestly say that GPT is more intelligent that a human being with an IQ of 100? What does this say about using simplistic metrics to assess a tapestry as rich and complicated as intelligence? Like everything else, intelligence has been subsumed into a worldview that quantifies everything.

In every age, humankind sees itself in the tools it uses. Iron Age paintings merge man with animal, the Renaissance saw the geometry of architecture in the human body, the steam age envisioned the mechanical body, and the digital age sees the brain as “hardware” with the “software” of thoughts. We look in the mirror and see what’s seared into our sight — the things we surround ourselves with.

The point of artificial intelligence when it was first propounded in the mid-twentieth century was not to replicate the outward signs of intelligence but to be intelligent. How? The secret of intelligence is an open-ended self-understanding that only human beings seem to be capable of.

You are a Strange Loop

This is where Douglas Hofstadter comes in. Hofstadter’s life work has been to make machines truly intelligent. Rather than replicating the signs of intelligence, Hofstadter dreams of a machine that could think about thinking as human beings do — a machine that can create meaning. But that entails understanding what intelligence actually is, not what intelligence looks or sounds like.

In his celebrated 1979 book, Gödel, Escher, Bach: The Eternal Golden Braid, Hofstadter claims to understand what the secret of human intelligence is, even the seemingly mysterious core of that intelligence — consciousness.

His stated stated aim in the book is no less than understanding what makes inanimate matter — the mass of particles that makes up the human body — the animate, intelligent, “large-souled” human being. His proposed idea is a polymathic feat — it’s what he calls “strange loops” that make intelligence.

According to Hofstadter, strange loops occur in hierarchical systems that are tangled and twisted by self-references. We experience a strange loop when we ascend or descend the hierarchy of a system only to find ourselves back where we started.

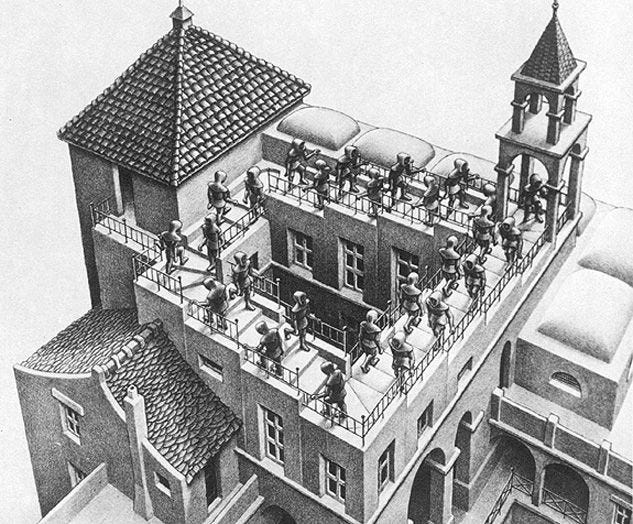

If you need something tangible to help you understand that idea, think of the paradoxical images of M.C. Escher, where people ascend a staircase only to find themselves at the bottom of the same staircase.

While the twisted, self-referential pictures of Escher and the compositions of J.S. Bach help us understand strange loops, the inspiration behind the idea of the strange loop is the twentieth century mathematician Kurt Friedrich Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems.

Gödel’s Theorems revolutionised mathematics because they have so far demonstrated that explanatory systems are inherently incomplete. If such a system is capable of self-reference, it will remain open-ended, much like human intelligence.

It’s beyond the scope here to fully elaborate the theorems, but in essence Gödel’s first incompleteness theorem is analogous to the “liar paradox”.

This paradox is the statement, “This sentence is a lie”. The sentence can neither be true nor false. If it is true, it is false, and if it is false, it is true.

The paradox is a loop in the tangled hierarchy of language. As we try to grasp this enigmatic sentence we ascend from mere words, through their meaning, to the validity of those words only to find ourselves back at the words again. This means that language is open-ended and can never be exhausted or foreclosed.

In his later book, I Am A Strange Loop (2007), Hofstadter wrote:

“I found the parallel between Gödel’s miraculous manufacture of self-reference out of a substrate of meaningless symbols and the miraculous appearance of selves and souls in substrates consisting of inanimate matter so compelling that I was convinced that here lay the secret of our sense of ‘I’”

For Hofstadter, thinking itself is a tangled hierarchy, and therefore it’s a system that is never complete, in the same way Gödel proved that no system capable of self-reference — like mathematics — can be complete. The incompleteness of the thinking mind gives rise to our consciousness — which Hofstadter simply believes to be more thinking, not anything special or different.

According to Hofstadter, the self is an ever-changing and never-complete neurological structure — which he calls a “self-symbol” — in the brain that is of course made up of the substrate of particles — pure matter.

When we consider those particles, we find the “self” — a high abstraction that emerges from the interaction of neurons, which in turn emerges from the interaction of particles. But when we breakdown the “self” we descend the hierarchy back down to the pure matter of the particles. Therefore, as Hofstadter puts it, “I am a strange loop”.

What gives us the feeling of an intangible self within the matter of our bodies then, according to Hofstadter, is the loops of our never-complete representation of our self in our thoughts. He wrote,

“what we call ‘consciousness’ was a kind of mirage. It had to be a very peculiar kind of mirage, to be sure, since it was a mirage that perceived itself, and of course it didn’t believe that it was perceiving a mirage, but no matter — it still was a mirage. It was almost as if this slippery phenomenon called “consciousness” lifted itself up by its own bootstraps, almost as if it made itself out of nothing, and then disintegrated back into nothing whenever one looked at it more closely.”

Having investigated the nature of human intelligence — what underlies the fluidity of human thought from the substrate of physical matter — Hofstadter is determined that a truly artificial intelligence can be created. This makes him something of a marginalised figure in the technology world, but also a figure more true to the Turing-era understanding of Artifical Intelligence.

In Hofstadter’s thesis there is nothing supernatural or exceptional about human intelligence and consciousness. Inanimate things can truly think if we can somehow give those systems the spark of self-reference, allowing them to think about their own thoughts. In this way, consciousness is to be thought of as a sliding scale, and, importantly, the measure of one’s “soul”. He wrote,

“more self-referentially rich such a loop is, the more conscious is the self to which it gives rise. Consciousness is not an on/off phenomenon, but admits of degrees, grades, shades. Or to put it more bluntly, there are bigger souls and small souls.”

Bounded in a Nutshell

There’s a number of problems with Hofstadter’s idea. The first problem is that Hofstadter believes intelligence to be located in the brain. In doing so he conflates mind and brain.

The mind is more than the brain. It surely includes the brain, but also the nervous system and also the nebulous system of symbols within your grasp — reminders on your phone, signs, books, post-it notes, notebooks, your calendar, files, bank accounts, TV shows… it goes on and on.

Is the mind also in the people you’ll likely meet in your lifetime? Probably. And it’s imbued in everything that you’ll come across that came before you, including the words you use to describe things.

It’s hard to draw a line around what “mind” is — it’s a word that’s surprisingly difficult to define, which is part of the point. The mind is part of an intricate, extensive, open-ended and changing network of the human culture in which we are embedded.

The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein believed that if a lion could speak English we wouldn’t understand it. This is because the lion’s language is embedded in it’s “form of life”.

In a number of interrelated arguments Wittgenstein argued that many problems we face is a result of the way language can bewitch us. We assume language to be a unified and transparent system of representation that’s processed in the privacy of our heads.

In reality, Wittgenstein argued, language is a public utility embedded in cultural practices — the meaning of words is not so much what they represent but their usefulness in particular contexts.

Intelligence is particular to a “form of life” — an amalgamate of biology and culture. It’s not just “in here” in the head, it’s also “out there” — beyond, before and after us.

This is why the refutation that AI can’t match our brains’ processing power is inadequate and plays into the hands of a debased notion of intelligence. It’s a refutation that implies — at least hypothetically — computers could catch up. But that’s a complete misunderstanding of intelligence — that intelligence happens in the brain.

An Achilles’ Heel: Consciousness

Hofstadter is right to claim that consciousness is thinking. But fails to adequately reflect on the innumerable ways we think. Thinking is not one thing, it’s a multiplicity.

The idea of the “self-symbol” at the heart of Hofstadter’s theory of consciousness only takes into consideration a narrow band in the wide spectrum of thought.

Phenomenological considerations are glossed over by Hofstadter’s course-grained view of our conscious selves. The self is more than a representation in the brain, it’s also a feeling that you cannot put words or symbols to — a feeling which is itself a form of knowledge, and it’s also the presence of our self in other people’s minds and the world around you.

Consciousness is a result of a multitude of mechanisms that help us survive and thrive in an environment that is in turns hospitable and hostile. These mechanisms vary in importance to consciousness, but no single one is tantamount to consciousness.

Like a political system there are necessary and unnecessary components of consciousness. The brain is a necessary component, as a legislator would be to a political system. Memories are part of consciousness but no one particular memory is essential, as is the case of particular voters in a political system — no one voter sways an election.

Part of the misunderstanding of consciousness is the analogies we use for it. Self-reflection is a misleading metaphor for consciousness. Self-reflection implies that the contents of the brain beholds itself, as a person would behold themselves standing before a mirror.

But consciousness is always directed at something, like light. Just as light cannot illuminate itself, consciousness cannot “know itself”. It utterly defies even consideration. It’s part of our thinking and our intelligence, but it’s not the kind of thought that can be described.

In being composed in this way, human consciousness is distinctly human. We are conscious in the way we are not only because of the size of our frontal cortex, but also because we suffer, because we’re recognised, because we’re watched, because we want to be loved.

We develop generalities to gravitate towards what we understand to be good and away from what we understand to be bad. The forces that compel, attract and repel us make us conscious as much as the internal workings of our biology.

There may well be other consciousnesses and these would be conscious in varying ways. Nietzche was probably right when he wrote that the mosquito floats through the air “with the same self-importance, feeling within itself the flying centre of the world.”

Human intelligence has the capacity to know itself, to apply syllogistic logic to its own thoughts. Insomuch as it can do that, it can construct the fiction of “the self”. But the self can only be a constructed fiction of the mind if consciousness makes it as such.

Consciousness is therefore transcendental. That’s not meant in a spiritual way — transcendential here means, “prior to, and necessary for, experience”. Consciousness is perfectly transparent, always directed at something, the plane of thinking.

Instead of thinking of consciousness as self-reflection, try this thought experiment.

Imagine standing between two parallel mirrors. As you stand aside, you see the mirrors repeating over and over, but they curve to the side. You want to see the reflected mirrors go on forever, so you position yourself in front of one of the mirrors again to witness this view of infinity. Doing so you realise that you are in the way, obscuring the view. It’s the same with consciousness — when we try to apprehend it, we see our “self”, not the consciousness that makes the self possible.

Our “self” — which Hofstadter is right to call a mirage or illusion — always gets in the way. It’s that “getting in the way” that shows that human intelligence has a basis in its form of life, which simply cannot be replicated.

That thinking is emergent, that it’s produced from many processes, makes it more, not less, elusive to artificial intelligence systems.

The technologies that we label as AI are tremendously useful — they’ll help us converse in different languages, they’ll fight crime, they’ll help us beat cancer, and they could even bring about world peace by predicting and helping to diffuse emerging conflicts.

They are also terrifying — AI is likely a threat to our specicies if systems are used irresponsibly. But they are not intelligent — not in the way we use that word to describe ourselves, and they never will be. Artificial Intelligence is a contradiction in terms. Intelligence is organic in essence.

If we think machines could think just as we do, we have a low opinion of ourselves. The extravagent claims made for the present and future of AI, debase our species and only further obfuscates our understanding of ourselves. It is corrosive in the present, and narrows the horizon of possibilities for the future. Our brains are not computers, and our thoughts are not software.

Some notes and references:

I used the English translation of Plato's demiurge - "craftsman" here for the sake of simplicity, I also used "heaven" as shorthand for the collective Platonic Forms. For more on Plato's creation myth, see Republic and Timaeus.

Hofstadter's books - both are brilliant, thrilling to read:

Gödel, Escher, Bach: The Eternal Golden Braid (1979)

I Am A Strange Loop (2007)

Source for Wittgenstein - Philosophical Investigations and The Blue Book.

Source for Nietzsche - “On Truth and Falsehood in an Extra-Moral Sense.”

Thank you for sharing