5 Philosophical Quotes to *Actually* Make You Think

These Ideas will Make you Question your Beliefs

Sometimes all it takes is a few words to shake up our world.

Even the best among us fall into a groove in life, we invest our emotional well-being in commonly-held assumptions. Our beliefs are shaped by our society’s norms and expectations.

These beliefs in turn shape the way we think and act, they underpin our values and how we account for ourselves. When things aren’t going right we’re left wondering why.

People are often intimidated by philosophy because it seems like a lot of complicated knowledge. But philosophy is an activity, not a collection of facts. Philosophy challenges us to evaluate everything we know. Just as intense exercise grows muscle, challenging our own ideas philosophically keeps our mind in a state of growth.

But like exercise, this can be uncomfortable. It’s not easy to examine your own beliefs and attitudes. But the pay off for doing so can be enormous. We can grow and flourish in all the relationships we have — as friends, partners, lovers, siblings, spouses and parents and citizens.

I come across quotes of philosophers and thinkers on social media feeds, ripped out of context and shared as vapid “wisdom” for likes and follows. Because of the lack of context, and because they are shared to please (and not to challenge), these quotes often actually stop us from thinking — they are rendered anodyne and neutral, making us feel smug and secure in our beliefs. We like them for their cleverness, but it’s cleverness for its own sake, rather than cleverness put to the purpose of actually thinking.

When we think deeply and philsophically, we break new ground. We see beyond appearence, we make novel connections. We privately innovate, which makes us publically more interested and more interesting.

Below I’ve picked a selection of philosophical quotes, with enough context, I hope, that will actually challenge you to examine your beliefs and values. Perhaps they’ll interest you enough to learn more. Perhaps this can be the start of something extraorinary for you.

“Man is the measure of all things.”

Protagoras (c. 490 — c. 420 BCE) from traditional attribution

Protagoras is painted as a bad boy of philosophy.

He was the first “Sophist”. This is a type of ancient teacher who charges money to teach well-heeled young men (this was Ancient Greece) how to be smart in the ways that will help them get by in life. Sophists like Protagoras taught the art of speech (rhetoric), argumentation, politics, and the general management of public affairs.

Teaching this kind of stuff was seen as unethical by Plato, more so charging for it. What disturbed Plato the most was the “relativism” of Protagoras’s teaching, such as the statement above.

“Man is the measure of all things” means everything we know is through human understanding.

This position is called “relativism” because to subscribe to it is to see no objective truth in the world, because human beings cannot access objective truth. Man is the measure of all things. We only know the world through the way we describe it.

To use a really simple example, two people may meet for coffee on a September morning. One is wearing a t-shirt and shorts, the other an overcoat and scarf. One says the weather is hot, the other says it’s cold. Their interpretation of the weather is different, but neither really reflect the objective truth of whether it is hot or cold. “Hot” and “cold” does not exist in nature. “Hot” and “cold” are human constructs.

Now extrapolate that basic example to the level of civilisation. If everything is a human construct and not an objective truth, what are the moral, legal and scientific foundations of our civilisations constructed on?

One culture may regard a practice — like capital punishment, abortion or polygamy — as evil, another may consider it as permissible or even good. What was moral or scientific “truth” in one period of history, may be a falsity in another.

Relativism is a dangerous idea. It’s like an acid that can burn through any container. In a world of no objective truth, how are we supposed to conduct ourselves ethically? How do we find meaning and purpose in our lives?

Well, there are two species of relativist. Firstly, there is the nihilist who believes in nothing at all, who holds that there can be no principles and values. A true nihilist would be a lone wolf by nature, since it’s a paradox to assert that the “truth” is that there is no truth.

Then there is the perspectivist, who rejects fixed, absolute or intrinsic principles and values but maintains that we can at least benefit from holding beliefs and values from our particular standpoint.

We have the compulsion to think and act and having contingent beliefs helps us fulfil those compulsions.

Think about it:

What ethical beliefs do you hold to be so certain that everyone else ought to believe the same thing?

How has your identity shaped those beliefs?

Would you believe the same things if you grew up in a differnt culture or age?

What makes those beliefs right?

“I know that I know nothing”

Socrates (c. 470–399 BCE) quoted in Plato’s Apology from The Last Days of Socrates

This is perhaps the most philosophical quote of them all. Reflective knowledge is so important, Socrates claims, that to discover you don’t actually know anything is a positive thing.

Examining one’s beliefs was an innovation of Socrates. Before the Athenian philosopher arrived in the fifth century BCE, what we call “pre-Socratic” philosophers were concerned with existence and the world. These philosophers were more like theologians or scientists — they had a mix of mystical and physical theories to account for our existence. Socrates was preoccupied with ethics. His philosophy sought to answer the question “what is the good life?”

The influential Oracle at Delphi declared Socrates to be the wisest man among them all. Socrates claimed to have been shocked by this pronouncement. He went about discovering what actually made him so wise. He spoke to many powerful experts on philosophy, religion and politics to understand what made them so wise.

But questioning powerful know-it-alls about strongly held beliefs and assumptions leads to trouble. The adversarial flavour of his questioning made him many enemies and Socrates was put on trial for corrupting the youth of Athens.

On trial, Socrates revealed why he thought the oracle pronounced him so wise. He discovered that, unlike the so-called experts and leaders he spoke to, he was willing to admit his ignorance. He said of one of his discussions:

“Although I do not suppose that either of us knows anything really beautiful and good, I am better off than he is — for he knows nothing, and thinks that he knows. I neither know nor think that I know.”

The key to the good life, as far as Socrates understood it, was wisdom. As you become wiser, you become a better person. Wisdom is not so much about knowledge — what you think, but rather about how you think. It’s about quality of thoughts, not quantity of information in your mind. To be wise is to understand what is important in life.

When everything is “bought and sold” for wisdom, Socrates claims, there will be true courage, true goodness, true compassion; all virtues will be “true”. Virtues without wisdom are just “stage-painting”, there is nothing “true” about them to Socrates.

Socrates summed up his legacy perfectly when he said,

“I try to persuade you, whether younger or older, to give less priority, and devote less zeal, to the care of your bodies or of your money than to the care of your soul and trying to make it as good as it can be.”

Think about it:

How much do you really know?

To be good people, what should we ought to know?

“If we possess our ‘why’ of life we can put up with almost any ‘how’.”

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) from The Twilight of the Idols

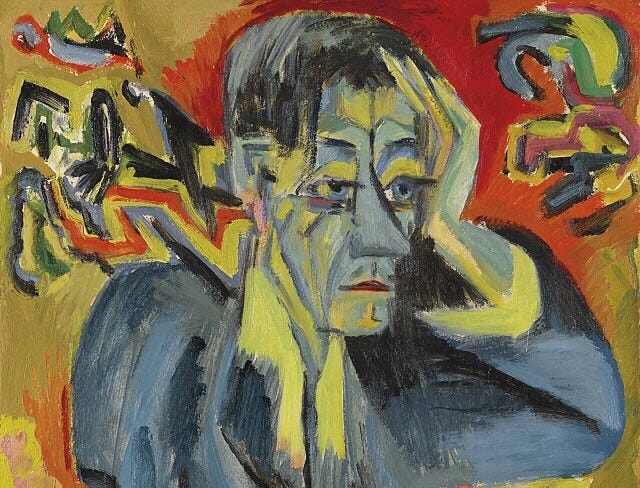

When Nietzsche wrote this, he was having serious problems with his declining mental health. He had alienated himself from friends and family, he was prescribing himself powerful painkillers to sleep. He had spurned the academic community, his books barely sold. The philosopher was on the verge of a mental breakdown that would incapacitate him.

His “why” kept him going.

In this maxim Nietzsche is referring, of course, to purpose. The philosopher was disturbed by what he saw as an epidemic of nihilism that had gripped European civilisation in his time.

Nietzsche thought that beliefs that had held western civilisation together were falling apart and all that would be left is lazy, nihilistic people whose lives are devoid of meaning and purpose, pursuing happiness for its own sake.

He foresaw how this nihilism would tear Europe apart. The rise of Nationalism, Fascism and Communism filled the belief vacuum and made the twentieth century the most destructive and bloody in history.

Merely living for enjoyment was for mediocrities. Happiness in itself is not a purpose. The philosopher joked, “Man does not strive for happiness; only the Englishman does that.” This is a swipe at the “English” philosophy of Utilitarianism, hugely influential at the time, which sought to achieve happiness for the greatest number of people.

Instead of following the herd, Nietzsche urges us to find meaning for our own lives and “self-overcome” through creativity to find true happiness and exuberance. This is is not easy of course, but as the philosopher explains in this gem of a quote, we can endure hardships when we have true purpose.

Victor Frankl, the psychologist who survived the holocaust and wrote Man’s Search for Meaning, paraphrased Nietzsche (unintentionally or not), when he wrote “A man who has a ‘why’ to live can bear almost any ‘how’.”

Frankl’s experience as a holocaust survivor, holding on to meaning when faced with the senseless horrors of the concentration camps, helped him develop his practice of logotherapy: the process of finding meaning in our lives.

Think about it:

What is your own “why” in life?

How much could you endure with the strength of this “why”?

“An ‘inner process’ stands in need of outward criteria”

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) from Philosophical Investigations

Everything we know about ourselves is a through a public utility called “language”. It existed before us and will outlast us.

Suppose you have a headache. You say to somebody “I have a headache”. How do you know that they know what you mean by that?

Wittgenstein uses a great example: suppose two people have small boxes, they can see into their own box but cannot peek into each other's boxes. They are told that they have a “beetle” in their box. And they can agree that they both have a “beetle” in their boxes, but neither of them truly know if the same thing is in the other box. The thing that is in each person’s box is irrelevant to the shared public meaning of “beetle”.

This is akin to the sensations we have in our bodies. While all this seems a bit trivial, and even silly, it’s actually a profound philosophical insight — intelligence doesn’t really reside in our minds.

We “know” our inner thoughts and sensations through the rule-governed medium of language. Most of us hold the assumption that the mind is like a private theatre. We tend to believe that we have an exclusively private, subjective view of the world. The data comes in from our senses and an “inner self” decides how to interpret that data.

But meanings are shared, not owned. Other language users are required to enforce the rules and norms of language use. Is a purely private language possible? Wittgenstein says “no”. Inner sensations — the “beetle” in the box to use Wittgenstein’s analogy — are senseless until they are made public. Our very sense of self is embedded in what Wittgenstein called “a form of life”. We are part of a connected grid, a node in a network.

Think about it:

How much do you know about yourself that you could not put into words?

How many people do you know who really understand the way you feel?

What is it that makes you so sure of that?

I would never die for my beliefs because I may be wrong.

Bertrand Russell (1872–1970), quoted in The New York Post in 1964 by Leonard Lyons

Bertrand Russell is one of the great philosophers of logic and mathematics, but also a great populariser of philosophy. His History of Western Philosophy is still a very popular reference book for people new to the subject.

At the age of 92 Russell was still an activist and campaigner for nuclear disarmament. Lyons, a columnist, asked him if he would die for his beliefs. “Of course not,” Russell replied. “After all, I may be wrong.”

We all hold beliefs. We hold many of them strongly. Some of them were formed in our own minds, while many others were handed down to us. We may believe that our country is great, we may believe that there is a God, that meat is murder, or the world is flat.

How much, when it really came down to it, would we wager on those beliefs? Our reputation? Our money? Our… lives? The kind of reason Russell is exercising here is “scepticism”, a word which comes from the Ancient Greek “Skepsis”, which means “to enquire”. Scepticism is different from relativism, it is less about truth and more about belief.

Scepticism is a principle which holds that beliefs are ultimately contingent. Beliefs can be useful, and beliefs enable us to organise our thoughts, and our societies, but beliefs can be wrong. Scepticism is particularly useful against dogmas and group-think. The sceptic is the one who stands apart from the mob.

Russell was passionate about his beliefs, he was jailed a number of times for protesting as a pacifist. But he was unwilling to defend them to the death. This isn’t about being brave, it’s about understanding the scope of our knowledge. Why wager the ultimate price on a belief that could be wrong?

Think about it:

What beliefs do you hold that you’d make big sacrifices for?

How true are those beliefs?

I hope these provocations have got you thinking. As I write this, I’m watching a fly bump against an open window. Like the fly, we also have our frustrations and upsets because we can’t see a way out. Many of our beliefs can be like the glass that “traps” the fly — views of the world that promise freedom, yet at the same time hold it back. Philosophy can help us find our way out.

Like meditation, philosophical contemplation is something anybody can do. It gives you the opportunity to pause and reflect on the contents of your mind, to take an audit so you can improve your thinking and develop as a human being.

It also makes you a better citizen of the world. As the world develops faster than our ways of explaining it, we need deep thinkers more than ever. There are many questions in life, and many more coming our way. The best answers are yet unwritten.

Thank you for reading. I hope you learned something new.

This post was originally written in 2019. Substantially edited and revised.